Tapping & Tubing

From Pails to Pipelines:

The origins of plastic tubing in the maple syrup industry

By PAUL POST | JUNE 26, 2022

BURLINGTON, Vt.—If the maple world ever creates its own version of Mount Rushmore, the tubing pioneers from the 1950s would make excellent candidates.

Nelson S. Griggs and George B. Breen of Vermont, and Robert M. Lamb of Central New York, led the way with development of plastic tubing for sap collection, which laid the foundation for today's highly-efficient, modern production systems.

Historian Matthew M. Thomas, PhD, discussed their work and the evolution of sap gathering in a fascinating online presentation, "From Pails to Pipelines: The Origins of Plastic Tubing in the Maple Syrup Industry."

Thomas created the website MapleSyrupHistory.com and has authored two books, "A Sugarbush Like None Other" and "Maple King: The Making of a Maple Syrup Empire."

"The invention and introduction of flexible plastic tubing was the result of a desire to find more efficient methods of gathering sap," he said. "Without the work of Nelson Griggs, George Breen and Robert Lamb we wouldn't have the type of tubing system the industry relies on today."

Briefly, Thomas told how for nearly 300 years sap was collected in pails, buckets and birch bark containers placed at the base of trees. From there, people had to carry it through the woods to a gathering tank pulled by horse, oxen or later on, tractors. "It was all labor intensive, everything done by hand," he said. "It was extremely difficult and tiring work, tedious at times, too, especially with snow, mud and hilly conditions."

But as early as 1794, there was an attempt to move sap with a crude pipeline consisting of wooden troughs nailed together. Garrett Boone, who lived near Cooperstown, N.Y., was strongly opposed to the cane sugar industry, which relied on slave labor. As an alternative, he tried to promote maple, a readily available rich natural resource.

Efforts at large-scale production failed, however, because his wooden collection system was plagued by cracks and leaks, and proved useless. Investors withdrew their support and the system was abandoned.

People kept innovating, though, and in 1863 Moses Shelden and Wareham A. Chase, of Calais, Vt., patented an improved wooden trough system. "This one was better than the one in New York because it was a single piece of wood, it didn't leach," Thomas said. "It was an effort to start moving this along."

Next, tubular metal pipelines, also called stand-pipe systems, came into play at some places from the 1860s to 1950s. "They were designed to move sap through the sugarbush from collection points to larger storage tanks," he said. "You still had pails on trees and you carried them to a stand-pipe dump spot (where sap was poured through funnels into metal tubes) and it would run downhill. It had problems, but it was definitely a labor-saving device, a major movement forward."

Thomas shared old photos showing the Horse Shoe Forestry Company's 50,000-tap system, which operated in the Adirondacks from 1896 to 1908.

Famous Jamaica, Vt. producers Helen and Scott Nearing, authors of "The Maple Sugar Book," developed their own stand-pipe system as they constantly worked at becoming more efficient moving sap through the sugarbush.

One of the next major advancements was a metal piping system, also called Gooseneck Tubing, developed by William Brower of Mayfield, N.Y. in the southern Adirondacks.

This was a big leap forward because it was a more complete system that routed sap right from the tree tap through laterals and mainlines, using a gravity-fed system, to collection tanks at the bottom of hills, sometimes right at the sugarhouse. Pails and collection tanks drawn by horses were no longer needed.

A gooseneck-shaped device connected taps to lateral lines. The system was laid out in a fashion very similar to today's plastic tubing.

"But it was a lot more expensive than taps and buckets, prone to freezing and slow to thaw," Thomas said.

Also, the somewhat-heavy system, suspended on wires, had to be laid out carefully because of its interlocking pieces of metal. Lines could be pulled apart by freeze-thaw cycles and easily damaged if bumped into, so maintenance was a constant issue.

Brower patented the system in 1916 and it was mass produced and used over a fairly wide area by larger sugar makers during the 1910s and 20s. A roadside state historical marker near Mayfield credits Brower for inventing "the first sap gravity flow tubing system from tree to sugarhouse for making maple syrup."

Plastic, invented in the early 1900s, became more widely used in the 1940s to help with the war effort during World War II. Its first application in sap collection was a product called the King Sap Bag, invented by Everett Soule of the St. Albans, Vt.-based George H. Soule Company. The clear, heavy duty bags were designed to replace metal pails. "But they had problems, they would crack and bust in the winter," Thomas said. "It would get brittle and break. But it helped open people's eyes to other opportunities for what plastic could do."

Griggs, Breen and Lamb were the men most responsible for developing flexible plastic tubing for maple sap collection. All three came from non-sugaring backgrounds, but their work revolutionized the industry.

Griggs, an MIT educated engineer from Montpelier, worked for Vermont State Highway Department and was also a consulting engineer for the Bureau of Industrial Research at Norwich University, in Vermont. The Bureau gave professional level engineering support to Vermont industries, especially start-ups trying to create new ways of doing things.

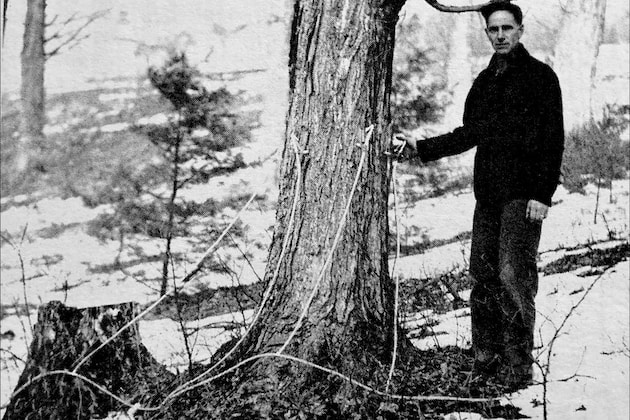

Through an acquaintance, Griggs got interested enough in sap collection to develop a sap gathering plan and led experiments at the Proctor Maple Research Center from March 8 to April 29, 1955. He developed metal taps with plastic tips that went a quarter-inch into drilled holes in trees. The other end went into tubing.

Taps on tubing, which fed into collection tanks, were twice as productive as open air taps on pails largely because tubing created its own natural vacuum that helped pull sap a little bit. Also, tubing with closed taps was more sanitary and eliminated some of the bacteria that would close a tap hole.

"They were satisfied that it was a successful technology," Thomas said. "Then they developed more sophisticated tubing systems where they connected tubing into tees. Ten trees, for example, could go into one collection point."

Griggs applied for a patent in February 1956 and a number of Vermont sugarmakers started installing his system, although its unclear where manufacturing took place.

Breen, another engineer, started working with tubing in 1953. He and his wife, Jackie, wanted to "get back to the land" and bought the Nearings' operation in Jamaica, Vt. The Nearings showed them how their metal pipeline system worked and taught them the basics of making syrup. "Pretty quickly Breen realized the metal system was still not the labor saving device he thought it should be so he started experimenting with plastic tubing," Thomas said.

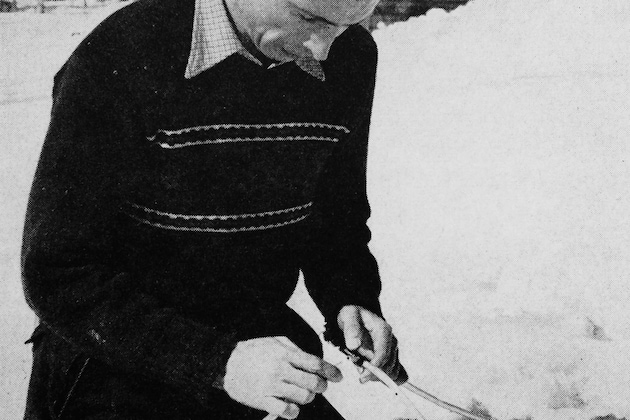

Before long, he caught the attention of the 3M (Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing) company, after he bought large supplies of its blood transfusion tubing. Breen inserted tubing into aluminum taps, which he had milled and got "pretty excited about how it was working," Thomas said.

A 3M executive convinced him to work with the company whose large resources could be used to develop a marketable product. The Mapleflo Brand Sap Gathering System became available in the fall of 1957 for use in the 1958 sugaring season.

Breen's job was to promote and sell the product around the state with a 5 percent commission on sales. Later, 3M offered him lump sump $25,000 buyout, which he accepted.

Even though Griggs obtained a patent first, Breen felt he might have taken some of his ideas because Griggs had visited Breen in 1954, a year after Breen began working with plastic tubing. The powerful 3M company applied its corporate muscle and threatened to challenge Griggs's patent. They also offered him $5,000 if he would agree not to file a counter-claim and cease developing such technology.

Griggs took the money and never worked with plastic tubing again.

Breen continued to operate his sugarbush until 1963 when he sold the farm and got out of the maple business. 3M became one of the first two makers of commercial plastic systems, which continued into the 1980s, although maple was a minor part of its large corporate business.

Lamb's family was running a chainsaw sales and marine small engine business in Liverpool, N.Y., near Syracuse, when he was approached by a Cornell Cooperative Extension forester, Dick Howard, who asked if he could come up with something better than a PVC pipeline an acquaintance was using.

The highly creative Lamb, always looking for new ways to improve things, showed off his work -- eventually called the Lamb Naturalflow Tubing Sytem -- during the 1956 New York State Maple Producers tour. "By late 1957 his system was completely intact and offered for sale for the 1958 maple season, the same timeline as 3M," Thomas said.

Lamb and his wife, Florence, left the family's chainsaw and marine engine business to focus full time on maple, but didn't obtain patents until the mid-1960s and never got into patent wars with 3M.

One of his most important innovations was a drop line that went to lateral lines laid on the ground. But the problem with this ground-based system is that it would get buried in snow, freeze and it was difficult to dig up if repairs were needed.

"It was a vented system that allowed air into tubing with the idea it would prevent vapor lock," Thomas said. "Bob thought an open system would be better, but research found that a closed system was needed to be more effective. As external vacuum was added you had to have a closed system. You couldn't build vacuum pressure with an open system."

But Lamb purchased an extruder and made his own tubing, producing tens of thousands of feet at his small family-run business. He constantly tweaked things, always trying to "build a better mousetrap" while corporate giant 3M devoted minimal time, energy and money to such work.

"Lamb became a major player and influential person in maple," Thomas said. "He worked hard and people respected that."

A handful of others such as Chester A. Wilson of Rock Springs, Wis.; Basil Hummer of Titusville Pa; George Butler, of Jacksonville Vt.; and Everett Soule of St. Albans, Vt., also worked with plastic tubing in the 1950s. But it was mostly for themselves and never became full-fledged commercial ventures.

Griggs, Breen and Lamb "were the ones who really got it going and became famous for developing plastic tubing that we know and people love today," Thomas said. "It proved to be a practical, efficient and cost-effective way to gather sap, which enhanced the outward flow of sap, created a longer season, allowed more control of sanitation and led to external vacuum. You couldn't do vacuum without tubing."