Vacuum & RO

High brix researched at Proctor Center

Sugarmakers should ask ‘How can I make this work for my place’

By PAUL POST | JUNE 9, 2017

New high-brix concentration reverse osmosis technology cuts fuel costs without sacrificing any of the flavor consumers look for in quality maple products.

But attempting to use it with an existing evaporator, is akin to putting a Hemi engine on your grandfather’s 1939 John Deere tractor — an exaggeration perhaps, but the point is clear.

You can’t just change one part of the processing equation. The latest RO equipment requires a whole new system.

That’s what industry experts said during the Jan. 21 Maple Conference with 125 attendees on hand at the SIT Graduate Institute in Brattleboro, Vt.

“If we used the same procedure we always used it didn’t taste like our maple syrup should,” said Glen Goodrich of Goodrich’s Maple Farm in Cabot, Vt.

The boiling procedure had to be altered, too, giving sap more time in the pans, allowing flavor to develop. “Using a modified evaporator with more flat pan and less flue pan, we were able to make the same flavor that we’ve always made,” he said. “So the end result is same flavor, done with less fuel. It’s simple, straightforward. We’re quite excited about it.”

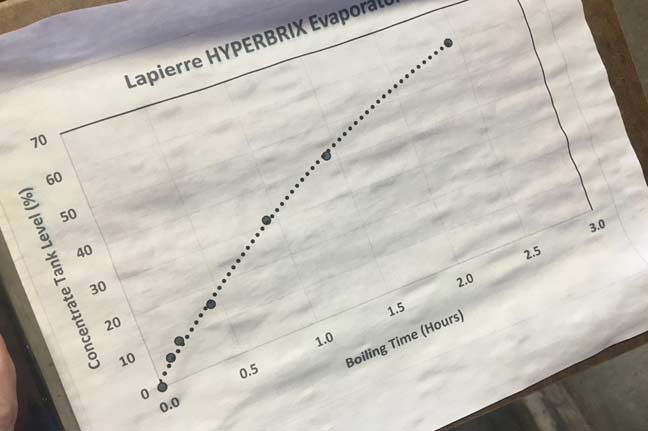

Lapierre HYPERBRIX and H20 Innovation Super-Concentrator are examples of two systems designed to handle concentrations of 35 percent or more.

But they might not be for everyone, Goodrich said.

“For a new startup or a sugarhouse that’s making a total change in equipment this makes all the sense in the world,” he said. “The payback will be pretty quick.”

The decision wouldn’t be as easy for someone with an expensive, existing evaporator and filtration system who might take a big hit trying to sell it used. This takes some real pencil sharpening to determine if switching out existing equipment is worth the investment financially.

There’s another important factor to consider, too.

“The main question is: How can I make this work for my place?” Goodrich said.

He uses RO and is a true believer about the benefits of high-concentration RO apparatus and has installed them for others. But he said high-concentration RO isn’t appropriate for his particular operation.

“Virtually everybody’s sugarhouse is predictable except mine,” Goodrich said. “At my place, I’ve got to be versatile. If I add taps or if a producer has had problems and wants to sell me sap, I can adjust the volume I can handle very easily. If I’m boiling from 40,000 taps this year, if I add another 20,000 next year I can still handle it.”

In contrast, high-concentration RO equipment is site specific, custom made for the size of the operation that’s buying it, Goodrich said.

“The RO can only process a certain volume. It’s designed and engineered to process that volume in a reasonable working day. Ideally we want to build it to handle that volume in a normal working time period, such as 10 hours. Then it needs a cleaning. The cleaning process for these machines takes a while. So doubling or adding 50 percent volume isn’t that easy to do,” he said.

Abby van den Berg, research assistant professor at the University of Vermont’s Proctor Maple Research Center, told how flavor experiments were conducted on syrup made from high-concentration RO equipment.

In previous decades, considerable research was done on brix concentrations ranging from 2 percent (raw sap) to 22 percent. In addition to scientific lab tests, for chemical composition, syrup was put through sensory evaluations (taste tests).

“All studies found that RO had no substructure impact on composition and particularly on flavor,” she said. “In all of the experiments where we conducted sensory evaluations of products, people said they could not detect differences between them. There was pretty solid evidence that RO had no impact, at least up to 22 percent concentration.”

The only difference is that RO had a slight to moderate effect on color. Up to 8 percent, the color got darker and the difference in color was greater in late-season syrup. At concentrations higher than 8 percent, color gets lighter, Van den Berg said.

With the arrival of new high-concentration RO equipment, researchers once again wanted to determine if flavor was impacted.

Pooling together an adequate supply of samples for physical testing proved prohibitively expensive, so this time researchers started with taste tests. Six producers provided three samples each from early, middle and late season.

The test compared both conventional and organic syrup against a control sample. Samples were placed in opaque containers so people couldn’t see the syrup’s color, which might influence their opinions.

The key questions were:

* Did they like it?

* Did samples have the characteristics of real maple syrup?

“That’s how we chose to approach it,” Van den Berg said.

In answer to the first question, 70 percent said they liked syrup made from high-concentration sap (including 4 pct., extremely much; 21 pct., very much; 26 pct., moderately). From the control samples, 68 percent of respondents said they liked the taste.

“So people were liking the syrups in the same amount,” Van den Berg said. “The control and high-brix concentrations were almost the same. We really have not been able to find an impact of RO on flavor.”

Answers to the second question were similar, with only a 1 percent difference in reactions to high-brix and control groups. “Results suggested that syrup made with high brix was both liked and characteristic of real maple syrup,” Van den Berg said. “RO isn’t doing anything weird to syrup. Flavor is similar to syrup of a similar color grade.

“You will make a lighter color syrup with this, that’s for sure, but it has the same characteristics of other light syrup.”

Research was made possible by the North American Maple Syrup Council Research Fund.

Goodrich said the flavor of his farm’s syrup has actually improved since regular RO was introduced. “We directly retail a lot of the product we make so flavor is a big factor for us. We also enter our products in lots of competitions to see how ours stacks up against everybody else. We’ve actually won more quality awards since we’ve gone to high-tech production. That’s really important to us,” he said.

His highly-efficient evaporator and mid-range RO uses about a quart of oil per gallon of a syrup made. “With high-brix production you can get that down to about one-tenth of a gallon of oil, but your electrical costs are up a bit,” Goodrich said. “The end result is total energy consumption is about half what it would be with a normal sugarhouse of today.

“For a system we installed last year, we found that the increased cost of the RO machine was offset by the decreased cost of his evaporation equipment. So the end result was, he didn’t have much additional cost to go to high-concentration. If an operator keeps everything clean, boils sap when he should in the right way, the quality is excellent.”