Headlines

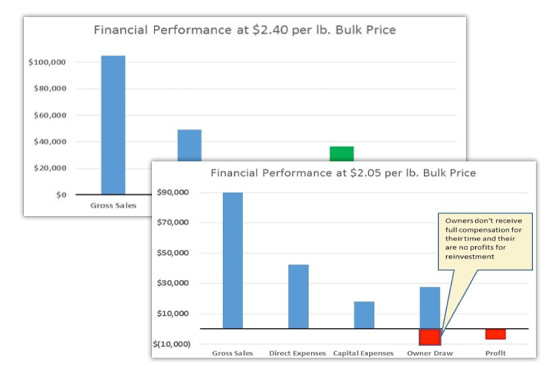

Low bulk prices squeeze the middle sized producer

Losses accrue with prices less than $2.05 per pound

By MARK CANNELLA, UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT EXTENSION | NOVEMBER 7, 2018

MONTPELIER, Vt.—Scale, production systems, and marketing have a major impact on how a maple business operates and performs.

These factors can impact profits, owner sanity, job creation, land use, and community footprint. “Right-sizing” gets used by business managers to determine the right scale a particular business can operate to accomplish its goals.

Most maple enterprises are unique and the concept of “right-sizing” recognizes that all aspects of an enterprise come to play. The number of taps is not the only factor in right sizing. Market outlets, prices received and management skills are all important.

As global maple production increases the markets, communities, and business owners are facing changes. Vermont, like many other US maple regions, has over a 150 year cultural heritage of syrup production ranging from subsistence production to commercial activity. A long maple history reminds us that there are many “right-sizes” for sugaring that satisfy the goals of the producers.

The declining bulk price over the past 3 years has forced many maple business owners that sell bulk syrup to question if they are or will be at the right size to stay viable.

Agricultural research has demonstrated how mid-scale farms can often get stuck in the middle of the push and pull of economics and consumer preferences (see “Food and the Mid-Level Farm” by Lyson, Stevenson, and Welsh).

The mid-scale maple business is likely to be a full time job for the owners for part of the year. These operators need to earn a livelihood from risky business activity.

They can sometimes be too big (or not well branded enough) to be accepted in niche markets and too small to compete with the big players. They take on debt from loans or borrowing from their own personal savings.

The maple producers in the middle are different than the very small operations that are set up as hobbies or lifestyle-type enterprises where profitability is not always a priority. The maple producers in the middle are also very different from the largest of producers that can produce syrup at very low costs, high volumes and have the staffing to coordinate the complex logistics of moving syrup into different market channels.

It’s important to realize that “size” is a subjective measure. The small, middle, and large for maple businesses may differ from region to region.

The recent maple price downturn has begun to reveal where the “middle bulk maple producer” may be in Vermont. The price downturn has shown how a reasonable owner livelihood and profit margin can disappear as the business environment shifts.

A small sample of 7,500-10,000 tap maple producers in Vermont from 2013-2017 demonstrates the looming risk. During average crop years the owners were able to draw a competitive wage, approximately $22 per hour for all hours worked, that added up to $30,000-$40,000 salary.

A small profit in addition to owner compensation was also created during an average crop year when prices were above $2.30 per pound. That profit could be put into savings or reinvested in the business.

It’s important to explain what “average crop” means here. These owners rely on this income for their livelihood and they are skilled operators averaging over 0.50 gallons (5.5 lbs.) of syrup per tap each year from 2012-2018.

This business model, however, cannot fully compensate owners and break-even if market prices stay below $2.10 per pound.

The same group of businesses at $2.05 per pound bulk price accrued losses over the past 2 years. Owners don't receibe full compensation for their time and there are no profits for reinvestment.

It is not easy for these 1-2 person businesses to pivot into niche direct marketing to sell their whole crop while still maintaining high level management of the tubing systems and sugarhouse.

Sugarmakers must be prepared for a tough year or two, but too many years without profits will force changes or business exit. A shift in scale, marketing plan, and overall management will be due quickly.

It is still too early to say exactly where bulk prices will be and how much volatility to expect. If prices rebound there will be many 7,000-10,000 taps that will hope to recoup recent losses and continue to operate in the middle.

If bulk prices hover close to $2.00 per pound then these same producers will be facing new decisions shaping the future of their business. The maple community will also need to recognize the changing face of the industry as new and different “right-sizes” emerge.